SeaBird admits wrongdoing on NewAge/Glencore seismic in Western Sahara

«We admit having done a mistake. It feels very uncomfortable having contributed in supporting an occupation power», seismic company SeaBird stated today. The company completed an assignment for Glencore and New Age in occupied Western Sahara in December.

Published 01 April 2015

The story below is an unofficial WSRW translation of the article "Svart gull kan bli slutten for fredsprosessen", published in Norwegian weekly Ny Tid, 1 April 2015.

The story shows how the Norwegian company SeaBird admits having done wrong by taking on the assignment in occupied Western Sahara. This is the fourth seismic survey company which regrets having entered the territory by mistake. The company stated to the newspaper it wished it had been in a financial situation last year which had allowed it to abandon the contract, once they found out what they were in fact doing.

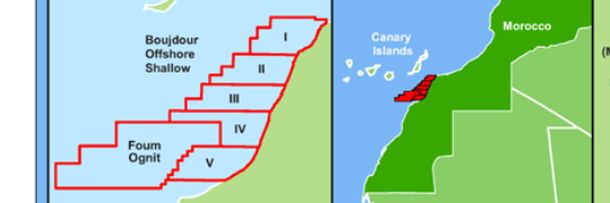

The map above, taken from a powerpoint presented by Glencore, shows the kind of information used by the licence holders to trick SeaBird into entering the deal. The Foum Ognit block is operated by New Age, and with Glencore with a 18,5% participating interest. No state in the world recognises the Moroccan claims to Western Sahara. SeaBird had ben told they were to work "in Morocco".

Black gold could be the end of the peace process

The Norwegian company SeaBird was involved in oil search offshore occupied Western Sahara. If oil is found, it is bad news for the Saharawis.

Early in the morning on 1 December 2014, an email arrives to Erik Hagen, director of the Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara. Activists in the association Western Sahara Resource Watch report that a vessel called «Harrier Explorer» is criss-crossing the seas between Las Palmas and the coastline of Western Sahara. Hagen seeks up the vessel on the website MarineTraffic, knowing that Moroccan oil authorities the later years have awarded licences to international companies in these waters. «Damn. Norwegians again», he writes back to WSRW. The owner of the vessel is the Norwegian seismic survey company SeaBird Exploration.

Violation of international law. After liberation from Spain in 1975, the country was occupied by Morocco. It led to a conflict between the occupiers from the north and the Saharawis, the people indigenous to Western Sahara. Inspite of continous peace talks between Moroccan governments and the Saharawi liberation movement Polisario, the occupation continues. Erik Hagen fears that the oil search makes the situation in the country harder. «A possible oil find in Western Sahara will make it even less likely that Morocco will enter into peace talks under UN auspices. The country does not produce oil itself and have large deficits on the state budget», Hagen told Ny Tid.

International conventions clearly establish that resource exploitation on occupied territory is illegal, and the Moroccan business in Western Sahara is therefore met with international condemnation. Several Norwegian companies have experienced that. When the Norwegian seismic survey company TGS-Nopec in 2002 took on an assignment for the oil companies Kerr-McGee and Total, it caused several stories in national media. Around 20 shareholders divested, among them numerous Norwegian municipalities, TGS-Nopec publicly regretted. In order to raise awareness on SeaBird making money on assignments in the occupied territory, Hagen made calls to the national media. The hope was that SeaBird was to be forced to abort the mission and withdraw from Western Sahara. But it turned out not to be so easy.

Near bankrupt. The last year’s falling oil prices has drastically reduced the number of assignmens in the international oil business. During 2014, SeaBird was forced to lay up two of its eight seismic survey vessels in Farsund. «The market conditions in 2014 made this year extremely challenging», CEO Dag Reynolds concludeed in SeaBird’s annual report, published 26 March. In September, the company was not able to meet loan repayments on 14.9 million dollars, and the company had to ask Oslo Stock Exchange to stop all trade on their stock. It was urgent to present a refinancing plan which the investors could accept. SeaBird was on the brink of bankruptcy. Few weeks later, a tender reaches Reynolds’ office desk: an assignment to shoot seismic surveys a place offshore Morocco. The assigjment was worth to million dollars, a relatively small amount in the oil business. But for SeaBird, all income was crucial.

«We had a vessel which was passing through the area, and the geographical description was offshore Morocco. To begin with, you respond that you are interested in the tender, then you discuss the commercial aspects, and then you get an assigment. We did not do any further investigations in terms of what and where»; Reynolds told NY Tid.

The block on which the work was supposed to be done is called Foum Ognit Offshore and was awarded the South African company New Age (African Global Energy) in December 2013, with Swiss Glencore Xstrata and Moroccan Onhym as partners. What Reynolds’ and his crew in Oslo had uncovered if they had done further investigations, is that this block is not in Morocco, but across the border, in occupied Western Sahara. However, such investigation was never part of SeaBird’s procedures associated to tenders. Reynolds told he was also not aware of the situation in Western Sahara upon the signing of the contract. «Only a small bell rang when I got to know about it. This is referred to as a forgotten conflict, and that was, regrettfully, the case for me», Reynolds told.

Not forbidden. After being contacted by a journalist in Dagbladet early December, Dag Reynolds contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to check whether the company indeed had violated intenational law by carrying out seismic in Western Sahara. They could inform that the assignment technically speaking is not illegal, but that they urge for caution. Reynolds informed the board and its president, former Orkla and Storebrand CEO Åge Korsvold, about the sitation. At this point, «Harrier Explorer» had already started the mapping of the controversial seafloor, and the company chose to proceed with the shooting. «We had rather not done this, because we knew we were doing something wrong. But we had ended up in a squeeze and felt we could not abandon the contract, since we were in the middle of a an agreement of refinance and on the brink of bakruptcy», stated Reynolds.

He said that if SeaBird had been in a more financially solid situation, they would have acted differently. But the period of decline in the oil industry had forced the bankruptcy threatened company into a corner where they had to make a difficult situation.

«If we had abandoned the contract, the oil company would have hired someone else to do the job, and we would have had to pay the extra costs for their mobilisation and demobilisation to the site. If we had said no, we would have been no more», he said.

Reynolds promises to never again shoot seismic studies in Western Sahara. If another tender comes from Morocco, the company will have systems to ensure they end up on the right side of the border, he claims. «We admit having done a mistake, and change our routines to prevent this from happening again. It feels very uncomfortable having contributed in supporting an occupation power», he said.

Steady course. The [Norwegian] Ministry of Foreign Affairs has over many years and changing governments given same answer to companies wondering if they can do business in Western Sahara. Norway is in line with the UN, as stated by the former UN Legal Counsel Hans Corell’s answer to the Security Council in 2002: «Just as with former governments, we discourage business and other activities in the territory which are not in accordance with the interests of the local population», deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Bård Glad Pedersen wrote in an email to Ny Tid.

«We do this because the unclarified satus of Western Sahara means that exploitation of resources in the territory according to international law must take place in accordance with the wishes and interests of the local population. The Government expects Norwegian companies to act responsibly when they invest abroad. If Norwegian companies choose to invest and carry out businesses in areas which the Norwegian government urges them to stay away from, they carry a high responsibility», he said.

Fears resumption of war. The behaviour of Morocco and international companies are well known for the the Saharwis. As late as last week, women, women and men in the Auserd refugee camps in Algeria held a peaceful demonstration against the companies that are buying up the natural resources of their homeland. After the occupation in 1975 many of them fled to the neighbouring country in the east. There, approximately 165.000 refugees still live under miserable conditions, waiting for a solution on the conflict. Erik Hagen in the Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara fears what will happen if the current situation continues. «The Saharawi people knows its rights as a people from a colonial territory. There are over 100 UN resolutions confirming their right to self-determination. The consequence of the oil search is that the Saharawis are increasinly angry. Morocco has no right to this oil. It is seen as extremely unfair, and it is a matter of time how long they will continue fighting with peaceful means», Hagen concludes.

News

Demonstrated against SeaBird/Glencore in Oslo

Saharawis and Norwegians gathered Thursday night in front of the offices of SeaBird in Oslo to protest against the company's oil exploration in occupied Western Sahara on behalf of Glencore and the Moroccan government.

20 December 2014

Expelled after doing interviews on Glencore-SeaBird oil exploration

A delegation from the Rafto Foundation for Human Rights was 10 December expelled from occupied Western Sahara by Moroccan police. The group entered the territory to discuss the Glencore-SeaBird seismic studies with local human rights activists.

13 December 2014

Western Sahara govt protests SeaBird seismic in occupied territory

The government of Western Sahara has sent a letter to SeaBird insisting on "an immediate end to the activity" of carrying out seismic studies on behalf of the occupying power in the territory.

12 December 2014

New Norwegian seismic study offshore occupied Western Sahara

The vessel "Harrier Explorer" is currently shooting 2D images of the seabed in the El Aaiun-Tarfaya basis offshore occupied Western Sahara.

08 December 2014