A Hong Kong company is linked to Morocco\'s brutal exploitation of Western Sahara. South China Morning Post, 10 August 2008.

South China Morning Post

By Ivan Broadhead

Aug 10, 2008

Download story in pdf.

Western Sahara's government-in-exile took the unusual step last week of warning Hong Kong's Pacific Basin Shipping that it reserved the right to use "all means" to defend its sovereignty and protect the interests of its people. The declaration was made as one of the shipping firm's vessels dropped anchor in Hobart to deliver a cargo of phosphate rock from Western Sahara's Boucraa minefields to Australian fertiliser manufacturer Impact.

Boucraa, home to some of the world's largest phosphate reserves, was seized along with the rest of Western Sahara in 1975 when King Hassan II ordered Moroccan troops to invade the former Spanish colony.

The annexation, joined by Mauritania from the south, was widely condemned but proceeded despite a ruling by the International Court of Justice that rejected any historical claim of Moroccan and Mauritanian sovereignty over the territory.

War ensued until 1981 when, Moroccan costs and casualties mounting, Rabat began building a 2,700km wall, or sand berm, across the Sahara. The wall continues to confine the Polisario Front - the Sahrawi (Western Sahara) liberation movement - to a sliver of territory along the Mauritanian and Algerian borders.

Notwithstanding a host of resolutions passed by the UN General Assembly calling for Sahrawi self-determination, "Western Sahara [remains] the last great decolonisation situation on the international agenda," according to Suzannah Linton, an associate professor in human rights law at the University of Hong Kong.

The Boucraa mines are operated by Morocco's Office Cherifien des Phosphates (OCP), a state-owned company and the world's largest phosphate producer. "They are plundering the wealth from our land," Mohamed Abdelaziz, president of the Sahrawi government-in-exile and Polisario secretary general, told the Sunday Morning Post from his headquarters in Algeria.

"Pacific Basin Shipping and other companies that participate in the exploration and exploitation of Western Sahara's natural resources should show some honour and respect, and cease acting as accomplices to the Moroccan government's illegal undertakings."

With perhaps 200,000 of his people living in Algerian refugee camps 33 years after fleeing the fighter jets and napalm of the Moroccan military, and the remainder trapped in a virtual police state inside the occupied territory, Mr Abdelaziz' demands for corporate social responsibility seem reasonable.

Pacific Basin's own CSR statement declares: "The group acknowledges its position as a responsible member of the community both in Hong Kong and in the cities and ports where Pacific Basin carries out its worldwide business."

While the company does not appear to contract directly with OCP, the suggestion that senior management's dealings with Australian and New Zealand fertiliser manufactures support a Moroccan regime that has variously been described as "brutal" and "repressive" will cause embarrassment to those well-known members of the local business community who sit on Pacific Basin's board - chairman David Turnbull, the former boss of Cathay Pacific Airways; chief executive Richard Hext, a former director of John Swire and Sons; and non-executive director Simon Lee Kwok-yin, Sun Hing Group chairman.

First approached six weeks ago to discuss the company's shipments out of Western Sahara, chief financial officer Andrew Broomhead insisted: "This is not a country we deal with."

When it was pointed out that New Zealand port authorities had recorded the arrival of the company's 52,000-ton Pacific Victory and its cargo of phosphate from Western Sahara just days before, Mr Broomhead issued a testy "no comment", adding: "I wouldn't know about such details."

In his only statement on the matter, deputy chief executive Klaus Nyborg acknowledged the Pacific Victory had called at Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara and the port nearest the Boucraa mines: "Pacific Basin operates in strict accordance with international laws and fully respects the terms of the United Nations regulations in relation to Western Sahara."

This assertion is absolutely correct. A 2002 report by Hans Corell, the UN undersecretary general for legal affairs, indicated that it was Morocco's exploitation of Western Sahara's natural resources that was illegal, where such action failed to benefit the interests of the Sahrawi. Pacific Basin's conveyance of these resources out of the territory does not contravene any law.

"This is not a `blood diamonds' situation," said Professor Linton. "There are no UN sanctions on trading with Morocco in relation to Western Sahara. [However] as an international lawyer I would advise Hong Kong firms not to deal with resources from the occupied Western Sahara.

"Corporate social responsibility is coming to play an increasingly important role in affecting the conduct of businesses and there is increasing litigation against [those] engaged in transactions that have dodgy human rights issues attached."

More important, argues Professor Linton, is to ensure that the Hong Kong government is prepared for the UN Human Rights Committee to scrutinise local firms' dealings with the natural resources of occupied Western Sahara at its next periodic review.

Such scrutiny would arise since, without any laws to regulate its corporations' behaviour in respect to trade with Morocco through the occupied territory, Hong Kong appears not to have complied with its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and other treaties to which it is a signatory, to uphold the Sahrawi right to self-determination.

The government could learn from Norway, Denmark and Sweden. In June 2005, the Norwegian government pension fund sold a nearly US$100 million stake in Kerr-McGee to show its disapproval of the US energy company's oil exploration in the occupied territory.

Research into the Ocean ID, the ship that Pacific Basin used for last week's voyage from Western Sahara to Hobart, revealed that the vessel is owned by a Danish consortium named K/S Danskib 54, formed by a firm named Investeringsgruppen Danmark (ID), and financed by Nordea Bank Danmark.

After hearing about the Polisario warning to Pacific Basin, ID was unwilling to comment about any concerns the ship's owners and insurers might have regarding the appropriate use of the vessel it had leased to the Hong Kong company.

However, only last month the Danish government issued the following guidance on commercial dealings involving Western Sahara: "Although the principles of international law and human rights are in general not directly binding for Danish companies, the ministry will at all times encourage Danish companies to be aware of their international responsibilities."

In light of this statement, it seems only reasonable to expect that ID will demand similar commercial standards be adhered to by Pacific Basin.

However, the temptation to trade with Morocco for Western Sahara phosphate is increasing. Processed into superphosphate fertiliser, it can improve crop yields by up to 50 per cent. As demand for food soars, so does phosphate demand.

Dana Cordell, at Sydney University of Technology's Institute for Sustainable Futures, estimates there will come a time, perhaps in the next 30 years, when maximum phosphate output is achieved - and then the world faces the prospect of tumbling agricultural output.

Phosphate prices are up more than 700 per cent in the past 18 months alone, to about US$400 per tonne, and are likely to rise further. People's Daily reports that, faced with recent natural disasters and concerns about next year's harvest, Beijing, to protect domestic phosphate supplies from overseas demand, raised export tariffs to 135 per cent in May.

Morocco, home to the world's largest reserves after China, would seem perfectly poised to cash in on the shortfall. OCP's profits are booming and output can be ramped up at mines including Boucraa.

This prospect angers Kamal Fadal, the Polisario representative in Australia. "As it is," he said, "the Boucraa reserves might only last another 30 years. The next generation of Sahrawi will be deprived of the resources to support their future."

Mr Abdelaziz, meanwhile, is compelled to make a final, more immediate plea to the good sense of companies such as Pacific Basin.

"The Sahrawi people must defend their legitimate rights," he said. "For 17 years we have done this in peace, through passive resistance. But by profiteering from our plight you demean the sacrifice of the Sahrawi. If we cannot achieve our aims peacefully, your actions compel us to consider other means ... including war. For all our sakes, please desist in this trade."

New report: Western Sahara phosphate trade halved

The export of phosphate rock from occupied Western Sahara has never been lower than in 2019. This is revealed in the new WSRW report P for Plunder, published today.

New report on Western Sahara phosphate industry out now

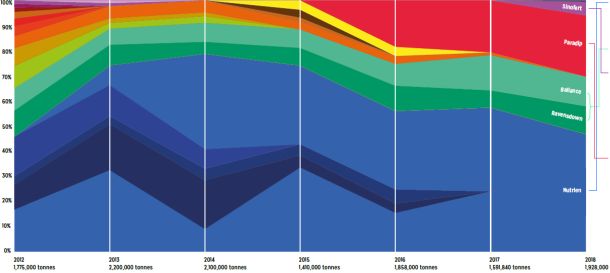

Morocco shipped 1.93 million tonnes of phosphate out of occupied Western Sahara in 2018, worth an estimated $164 million, new report shows. Here is all you need to know about the volume, values, vessels and clients.

New report on contentious Western Sahara phosphate trade

Morocco shipped over 1.5 million tonnes of phosphate out of occupied Western Sahara in 2017, to the tune of over $142 million. But the number of international importers of the contentious conflict mineral is waning, WSRW's annual report shows.

New report on global phosphate trade from occupied Western Sahara

Over 200 million dollars worth of phosphate rock was shipped out of occupied Western Sahara last year, a new report from WSRW shows. For the first time, India is among the top importers.