A packet of cherry tomatoes sold this week in a French supermarket illustrates the confusion triggered by the European Commission’s rushed attempt to adapt EU consumer and trade rules to Morocco’s claims over occupied Western Sahara.

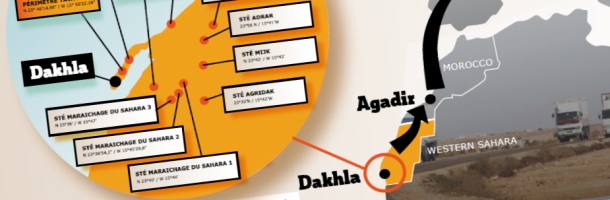

Photographed on 13 November 2025 a Lidl supermarket in the Rhônes-Alpes region, France, the package lists the origin of the cherry tomatoes as “Dakhla-Oued Eddahab” - a Moroccan administrative region created by Rabat on occupied Western Sahara territory after it illegally annexed the territory in 1975.

Under current EU law, however, products originating from the territory must still be labelled “Western Sahara”. The EU Court of Justice (CJEU) has repeatedly confirmed that Western Sahara is “a separate and distinct territory” from Morocco, and that EU agreements with Morocco cannot apply there without the consent of the people of Western Sahara. This also affects how origin must be indicated: products from the territory cannot be presented as Moroccan, the Court ruled.

So how did this peculiar mislabelling happen?

On 4 October 2024, the CJEU once again annulled the EU-Morocco trade agreement insofar as it applied to Western Sahara, ruling that it violated the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination. The Court allowed the deal to remain provisionally in force for one year, until 4 October 2025, giving EU institutions time to bring practice in line with the law.

Instead of seeking the consent of the people of Western Sahara to an arrangement covering trade with their occupied homeland, the EU Commission chose to re-negotiate the same type of agreement with Morocco, and in a highly irregular rush: the amendment was supposedly negotiated within four days in September 2025.

While ten CJEU rulings leave no doubt that Western Sahara is not part of Morocco, and that products from the territory must be treated accordingly, the EU’s new agreement accepts the replacement of the concept of “country of origin” with that of “region of origin” when goods come from Western Sahara - specifically, the two administrative divisions Morocco imposed on the territory: Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra and Dakhla-Oued Eddahab..

These names were specified by the EU-Morocco Association Council in Decision No 2/2025 of 3 October 2025, which instructs that they be used in certificates of origin and in origin declarations. MEPs in the EU Parliament’s International Trade Committee have already expressed concern at what they described as a deliberate attempt to bypass the legal status of the territory.

According to the Commission’s own notice to operators, published on 16 October 2025, the new system will only apply once its newly proposed Delegated Regulation enters into force, after which it will apply retroactively. Until that moment, current EU marketing standards remain fully applicable - meaning origin must still be labelled “Western Sahara.”

The same notice also tells operators that stock already labelled “Western Sahara” may continue to be sold until exhausted. But it offers no clear instruction that the Moroccan regional names cannot yet be used. This has already led to the mislabelling now appearing on French shelves, illustrating the practical fallout of the Commission’s decision to advance a politically sensitive change without legal clarity and before the regulatory process is complete. The result is uncertainty for consumers, traders, and authorities - with operators violating EU law without even realising it.

This confusion is not a trivial administrative glitch. It stems directly from the Commission’s choice to rush through a politically motivated and legally questionable change to the EU’s origin-labelling rules.

Amending a general EU law for one political exception

But it gets even murkier. To implement its new labelling approach for Western Sahara products, the Commission seeks to amend Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2429 - a general regulation that sets marketing standards for all fruits and vegetables across the EU and in third-country trade.

That regulation, in force since 1 January 2025, was meant to simplify rules, strengthen consumer information, and reduce food waste. Instead of protecting this uniform framework, the Commission is now carving out an exception for the very singular case of occupied Western Sahara, bending an EU-wide framework to accommodate Morocco’s unfounded territorial claims.

This is an extraordinary move: rather than applying established EU geographical nomenclature, the Commission seeks to insert Morocco’s administrative divisions of an occupied territory into general EU law, contradicting a decade of CJEU jurisprudence affirming that Western Sahara and Morocco are separate and distinct territories.

“If the EU is now willing to rewrite general legislation to suit the preferences of an occupying power in Western Sahara, what stops it from doing the same for Crimea, or for the Palestinian territories that Israel designates as Judea and Samaria?”, asks Sara Eyckmans from Western Sahara Resource Watch.

The matter is now formally on the agenda of the European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee on Thursday, 20 November, where MEPs will discuss the Commission’s proposed amendment to the marketing-standards regulation. The mislabelling seen in France demonstrates that the Commission’s approach is already generating practical and legal problems before the proposal has even been approved.

Since you're here....

WSRW’s work is being read and used more than ever. We work totally independently and to a large extent voluntarily. Our work takes time, dedication and diligence. But we do it because we believe it matters – and we hope you do too. We look for more monthly donors to support our work. If you'd like to contribute to our work – 3€, 5€, 8€ monthly… what you can spare – the future of WSRW would be much more secure. You can set up a monthly donation to WSRW quickly here.

Report: EU consumers unwittingly supporters of occupation

The WSRW report ‘Label and Liability’ documents how produce from the controversial agro-industry in the occupied territory, ends up in the baskets of unaware EU customers.

WSRW report reveals massive agri-industry in occupied Western Sahara

The new WSRW report ‘Conflict Tomatoes’, launched today, reveals massive growth in the Moroccan agriculture industry in occupied Western Sahara and its trade to the EU.

Farmers block Azura warehouse in France and launch legal action

Growing pressure on EU–Morocco trade deal as French farmers today launch legal steps and storm Azura’s entry point for Western Sahara produce in Perpignan.

First season in Switzerland without occupation tomatoes?

From this winter on, Swiss supermarkets will probably, for the first time, no longer sell tomatoes from occupied Western Sahara.