Peak P

In approximately 30 years, as production from the world’s phosphate rock reserves reaches a maximum, Western Sahara’s geopolitical importance will become even more important. Australian researcher Dana Cordell investigates ‘peak phosphorus’.

Published 22 July 2008

“The world population is addicted to phosphorus, just as we are addicted to water or energy. We will always need it to produce food”, explains Dana Cordell, PhD candidate at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology, Sydney.

“But current global phosphate rock reserves could reach a maximum in production in only 30 years. Then what?”, asks Cordell.

“But current global phosphate rock reserves could reach a maximum in production in only 30 years. Then what?”, asks Cordell. Despite phosphorus being a crucial part of the world economy, there is almost a complete lack of international discussion on phosphate scarcity in the world, or about its strategic geopolitical importance, according to Cordell.

Phosphorus (P) is a chemical element that is normally found in phosphate rock. Morocco is the biggest phosphate rock exporter in the world, and much of it is exported from occupied Western Sahara in violation of international law.

Cordell and her research colleagues have this week launched a new website, www.phosphorusfutures.net, dedicated to fostering debate on the environmental sustainability and on the geopolitical play involved in the production and management of phosphorus resources.

The website is part of the Global Phosphorus Research Initiative (GPRI), a joint research project between the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), and the Department of Water and Environmental Studies at Linköping University, Sweden.

The prices that sky-rocketed

The last 15 months have seen more than a 700% increase in global phosphate rock prices. But this could be only the beginning. Cordell believes the price is likely to continue rising in the years to come.

One of the reasons for the past year’s price hike, is that there are more mouths to feed. Secondly, particularly in emerging economies like China and India, there is a rapid change in people’s diet, whereby consumers are eating more meat and dairy, which is generally far more phosphorus intensive than producing grains or vegetables.

A third reason is that the phosphate price now is affected by the increasing oil price.

“The current oil crisis has increased the general understanding that petroleum is a non-renewable and unsustainable resource. As a response, the market has developed alternative energy sources, such as biofuels, which many believe are renewable and respond to the limitations of petroleum. But many people have not realised that production of biofuels is dependent on fertilizers. And fertilizers are today completely dependent on another non-renewable and unsustainable resource, phosphate rock”.

So the increased biofuel production has not only led to higher food-prices, but also a sudden increase in prices of phosphates.

But the worst could be yet to come

Phosphate rock reserves are highly geographically concentrated, and thus only exist under control of a small number of countries. The biggest are China, Morocco (who controls Western Sahara's reserves), and the US.

But China and the US struggle even to meet their own demands.

China has recently imposed a 135% export tariff to secure domestic fertilizer supply. This is likely to halt most exports from China. Simultaneously, US supplies keep getting smaller for every year. US used to be the biggest producer of phosphate rock. But now they have maximum 20 to 30 years left of their own phosphate rock deposits.

China has recently imposed a 135% export tariff to secure domestic fertilizer supply. This is likely to halt most exports from China. Simultaneously, US supplies keep getting smaller for every year. US used to be the biggest producer of phosphate rock. But now they have maximum 20 to 30 years left of their own phosphate rock deposits. According to the US Geological Survey, US has for a number of years received 99% of their imported phosphate rock from Morocco/Western Sahara. At least since the end of the 80s, US has remained the biggest importer of phosphates from occupied Western Sahara, despite the fact that it is in violation of international law.

“With US and China tightening its grip around their owned mined phosphates, and as the phosphate prices will continue to grow, the mines in Morocco and occupied Western Sahara will become increasingly important for world phosphate importers and for the global agriculture industry.”, Cordell says.

“Western Sahara’s phosphate reserves will become a real gold mine for Morocco in the future”, Cordell says.

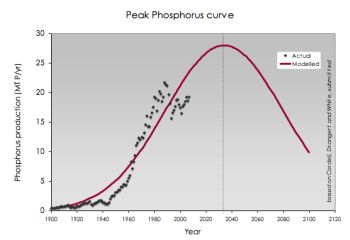

Estimations from Cordell and her colleagues suggest that the phosphate production will peak around 2040. That is about same period as the proven deposits in occupied Western Sahara will come to an end.

Find alternative sources

While oil and other non-renewable natural resources can be substituted with other sources when they peak (like wind, biomass or thermal energy), phosphorus has no substitute in food production.

“We will always need phosphorus. But it does not need to come from phosphate rock”, Cordell says.

Studies carried out in Sweden and Zimbabwe shows that nutrients in one person's urine is sufficient to grow 50-100% of the food requirements of another person.

Follow GPRI’s research on this on www.phosphorusfutures.net

News

Australia finally finished phosphate imports

The last remaining importer of phosphate rock from occupied Western Sahara in Australia has announced that it will no longer purchase the conflict mineral.

08 July 2025

Japanese conflict mineral importer identified

WSRW has traced the imports of phosphate rock to a dock just adjacent to a subsidiary of Japanese company Taiheiyo Cement Corporation.

16 June 2025

These are the clients of Morocco’s phosphate plunder

For the eleventh year in a row, Western Sahara Resource Watch publishes a detailed, annual overview of the companies involved in the purchase of conflict phosphates from occupied Western Sahara.

22 May 2024

COWI abandons future projects in Western Sahara

After undertaking work for the Moroccan state phosphate company in Western Sahara, the Danish consultancy giant COWI states that it “will not engage in further projects" in the occupied territory.

11 March 2024