The German building materials giant sides with Morocco in the Western Sahara conflict, avoiding any questions on its own legal obligations in the occupied territory.

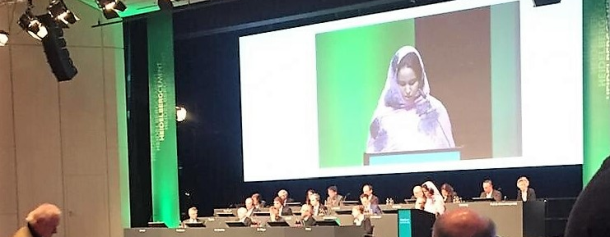

HeidelbergCement dug in its heels on occupied Western Sahara at its Annual General Meeting of 6 May 2021.

The German company controls two cement factories in Western Sahara through its Moroccan subsidiary Ciments du Maroc (CIMAR) on permits issued by the government of Morocco, which illegally occupies the larger part of the territory.

Instead of answering questions from shareholders pertaining to the legal status of the territory, HeidelbergCement submitted that its activities are to the benefit of the “local population”.

The “benefits” argument has been squashed by the Court of Justice of the European Union in its judgment of December 2016, ruling that the EU-Morocco Trade Agreement could not be applied to Western Sahara, as the territory is separate and distinct from Morocco, and the latter has no mandate whatsoever to administer the territory. The Court stated it is irrelevant whether the agreements are beneficial to the people of Western Sahara, what matters is that the people have actually consented to them. Through the relative effect of treaties, that reasoning also applies to contracts.

A transcript of HeidelbergCement's answers to questions submitted by Dachverband der kritischen Aktionärinnen und Aktionäre, in collaboration with Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW), can be found here: English version, and original German version.

HeidelbergCement's response to the question as to whether it has sought the consent of the people of Western Sahara, received a most confusing response. On the one hand, HeidelbergCement's response at the AGM was that “we assume that the local population agrees with our business activities”. On the other hand, the Board's statement on the Western Sahara countermotions reads that “Already during the planning of investment projects, in addition to comprehensive social and environmental impact assessments, a broad engagement of all stakeholders takes place, which takes into account the special concerns of indigenous groups, as well as the concerns of other local residents. The principles of free, prior and informed consent are taken into account in all projects.”

This type of statement is obfuscating on the issue of consent, as there is a fundamental difference between the principle of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous groups - who recognise the State in which their land is located - and the right to consent stemming from the right to self-determination of a people from a non-self-governing territory under occupation. The Saharawis are not an indigenous group in Western Sahara, they are the people holding the sovereign rights to the land. And HeidelbergCement has never asked them anything. The firm admits it has never approached the UN-recognised representative of the people of Western Sahara, the Polisario Front.

HeidelbergCement opines that Polisario has “only been recognised as a political representation for issues of international law." The company went on to state that it regrets that “Polisario has refused a negotiated solution within the framework of the UN process in place and has instead called off an existing ceasefire. International humanitarian law states, among other things, that neither the civilian population as a whole nor individual civilians may be attacked. We expect that Frente Polisario respects the statutes of international humanitarian law.” The firm remains silent about the fact that it was Morocco that violated the ceasefire by attacking civilian Saharawis.

Yet when it comes to HeidelbergCement's own activities and how they relate to international humanitarian law, the company considers it a non-issue that it is operating on and exporting from occupied land without consent of the people: “About two thirds of the products are sold in El Aaiún and the surrounding area, the rest is exported to Morocco, so there is no conflict with norms of international humanitarian law.”

A countermotion was also presented by Wespath Benefits and Investments, which stated that “HeidelbergCement's Managing Board has provided insufficient information to investors on its efforts to align its business practices and human rights due diligence with the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD).” Referring to Morocco as “the occupying power of Western Sahara”, Wespath's counterresolution stated that “occupying powers may not exploit resources without the consent of the occupied population” and that “we are unaware of any consent received from the occupied population. Hence, the company may be contributing to violations of IHL."

HeidelbergCement's subsidiary Ciments du Maroc (CIMAR) holds a majority stake in the CIMAR cement grinding company, and it took over Cimenteries Marocaines du Sud (CIMSUD) in May 2020. Both are located in El Aaiún, the capital of Western Sahara.

These factories likely provide the basic material for Morocco's continued settlement policy in Western Sahara. According to the research services of the German Bundestag, Morocco's settlement policy constitutes a war crime. In November 2020, Morocco violated the UN-brokered ceasefire arrangement in the territory, leading to resumed armed struggle, which in turn resulted in an uptick in repression by Moroccan security forces of Saharawi civilians - a deterioration of an already dramatic human rights situation.

'We deserve an answer' from HeidelbergCement

When requesting answers on human rights from HeidelbergCement with regard to its operations in occupied Western Sahara, Saharawi Khadja Bedati was told that the company "deliberately makes social sponsoring of various sports clubs".

UK company building wind park in occupied Western Sahara

Morocco and Siemens press on with their plans to generate energy in the human rights black-spot that is Western Sahara: the first controversial wind farm near Boujdour is expected to be operational in December 2018, built by a UK company.

New controversial energy infrastructure to be built in Western Sahara

The Moroccan government has opened for a relatively large tender in Dakhla.

Report: Moroccan green energy used for plunder

At COP22, beware of what you read about Morocco’s renewable energy efforts. An increasing part of the projects take place in the occupied territory of Western Sahara and is used for mineral plunder, new WSRW report documents.