Growing fruit and vegetables in the desert destroys the non-renewable water reservoirs and employ thousands of settlers from neighbouring Morocco.

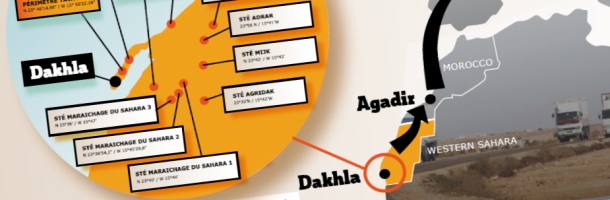

Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW) has so far identified 12 agricultural sites in the vicinity of the Dakhla peninsula, located along the mid-coast of occupied Western Sahara. Tomatoes and melons are the main crops in the area, with cherry tomatoes - yielding between 80 and 120 tonnes per hectare - taking up the lion's share of production, destined for export. Today, four big agro-operators cultivate the Dakhla plantations; Rosaflor, Soprofel, Azura and Les Domaines Agricoles. All of these are either owned by the Moroccan king, powerful Moroccan conglomerates or by French companies, selling their produce under brand names as Azura, Idyl, Etoile du Sud and Les Domaines Agricoles.

From 2021, it was known that some of the same companies are also starting up blueberry production in the occupied territory.

Morocco has turned the agricultural industry in Western Sahara into a driving force for populating the territory with Moroccan settlers. As confirmed by a member of the Moroccan parliament who co-owns a farm in Dakhla, workers are brought in from Morocco.

Agriculture in the desert is not a sustainable undertaking: it is incredibly water intensive. The underground water reserves in the area around Dakhla, which ought to be used for the benefit of the people living there, are being depleted by the agro-industry - as also confirmed by leaked US Diplomatic cables.

The products are found in supermarkets all over Europe. Several European chains, such as in Switzerland, Sweden, Finland and Norway, have explicit policies preventing them from purchasing agriculture products from Western Sahara. A challenge for importers has been that the tomatoes produced in Dakhla are transported to Agadir overland, where export units both treat tomatoes grown in Morocco proper, as well as the ones produced in Dakhla.

The French company ENGIE has been commissioned by the Moroccan government to erect a desalination plant for the industry. To defend its operations, ENGIE refers to a controversial study undertaken by the company Global Diligence.

Since the turn of the century, the Dakhla plantations have been booming. From 2003 to 2005, about 150 ha of agricultural infrastructure was in use. By 2010-2012, the acreage had risen to 841 ha. By 2016, an estimated 963 ha was in use. Read WSRW’s research note “The expansion of plantation infrastructure in occupied Western Sahara 2003-2016”.

The timing of the first agricultural boom is remarkable. The large increase in cultivated acres occurred at the time when Morocco and the EU were negotiating an expansion of the EU-Morocco trade agreement, liberalising the trade in fruits and vegetables. The Moroccan government and the Moroccan/French companies involved had seemingly expected the trade agreement to go through. After all, the EU is the main market for the agriculture products grown in Dakhla, as documented in WSRW’s 2012 report "Label and Liability".

The deal, often referred to as the EU-Morocco 'agriculture agreement', entered into force in October 2012. Just a few weeks later, in November 2012, the representation of the Saharawi people, the Frente Polisario, brought action against the EU Council, asking for the annulment of the Council decision concluding the agriculture agreement with Morocco. In December 2016, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that Western Sahara was a territory that is “separate and distinct” from Morocco, and that as such no trade or association agreement with Morocco could be applied to it, without the express consent of the people of the territory: the Saharawis.

The judgment angered the Moroccan government. On 6 February 2017, Morocco's Minister for Agriculture released a statement warning that any obstacles to his country’s agriculture and fishing exports to Europe could renew the “migration flows” that Rabat had “managed and maintained” with “sustained effort.”

The European Commission responded in blatant disrespect of the EU Court's judgment and commenced negotiations with Rabat to secure its imports from Western Sahara within the framework of the EU-Morocco trade deal. An amendment was introduced to the agreement, explicitly including Western Sahara in its geographical scope. The Saharawis were not asked a thing. Instead of seeking their consent, the EU Commission undertook a consultation of representatives of Moroccan political institutions and businesses. Saharawis expressed their opposition to the deal via both the Frente Polisario and civil society groups – which the EU Commission then falsely presented as though it had consulted Saharawis. In 2020, WSRW wrote a report on the renewal of the agreement.

The amended trade deal is now again subject of legal proceedings with the EU Court of Justice.

Opposition to the EU’s agricultural imports from Western Sahara not only comes from the people of Western Sahara, but also from European farmers. Particularly farmers of southern European countries, such as Spain, have raised "concern about the increase in the volume of productions imported from Western Sahara as Moroccan products. They cause great damage to Spanish producers since those volumes overlap with our production schedules and are intended for the same markets."

The Spanish farmers' association noted that exports from Western Sahara to Europe would constitute "unfair competition, given their lower costs based on very permissive regulations when it comes to the working conditions, social coverage and wages of workers, or the application of phytosanitary, safety and food quality regulations, etc. Moreover, it is also a case of fraud for European consumers, whose rights are not respected since they will not have reliable information on the real origin of those imported fruits and vegetables."

When a revised EU-Morocco trade agreement for agriculture products was pushed through in the EU Parliament's agriculture committee in 2018, the committee noted that such deal with Morocco would have only negative aspects for the EU's farmers. Yet, they voted for in favour of it. Read more about that strange vote here.

Since you're here....

WSRW’s work is being read and used more than ever. We work totally independently and to a large extent voluntarily. Our work takes time, dedication and diligence. But we do it because we believe it matters – and we hope you do too. We look for more monthly donors to support our work. If you'd like to contribute to our work – 3€, 5€, 8€ monthly… what you can spare – the future of WSRW would be much more secure. You can set up a monthly donation to WSRW quickly here.

WSRW report reveals massive agri-industry in occupied Western Sahara

The new WSRW report ‘Conflict Tomatoes’, launched today, reveals massive growth in the Moroccan agriculture industry in occupied Western Sahara and its trade to the EU.

Is your local shop selling conflict tomatoes?

Morocco’s tomato export season starts today. But some of the ‘Moroccan’ tomatoes you’ll soon find in your shop have been grown illegally in a territory under military occupation. Have you spotted dirty tomatoes? Help us to identify them in your local store!

Report: EU consumers unwittingly supporters of occupation

The WSRW report ‘Label and Liability’ documents how produce from the controversial agro-industry in the occupied territory, ends up in the baskets of unaware EU customers.

The tomato barons of the occupied Western Sahara

Who benefits from the booming agricultural industry in occupied Western Sahara? Surely not the Saharawis.